Come la Neurogastrofisica (ovvero come le neuroscienze) spiegano la gradevolezza del vino

**The translation is at the buttom**

Il sapore di un vino può essere modificato da aspetti che nulla hanno a che fare con il prodotto stesso? Ovvero la qualità percepita di un vino può essere modificata da elementi esterni al prodotto, come per esempio la musica di sottofondo o il contatto con un sottobicchiere ruvido (di carta vetrata nera) o morbido (di peluche bianco)? Come dicono alcuni noti neurobiologi Morrot, Brochet e Dubourdieu (2001), “il gusto di una molecola o di una miscela di più molecole si costruisce nel cervello di un assaggiatore”. In effetti il sapore del vino può essere influenzato da aspettative e condizionamenti che nulla hanno a che fare con le nostre papille gustative.

In questo ambito sono state condotte numerose ricerche: dall’effetto dei colori di un vino alle luci del luogo in cui si degusta, dalla musica di sottofondo in fase di assaggio alla forma o alla consistenza del bicchiere. Al tal proposito, ricordo quando durante una splendida degustazione di vini rossi, presso la Cantina del Baglio del Cristo di Campobello in Sicilia, il proprietario ci fece degustare un medesimo vino in due bicchieri, uno di vetro normale e uno di nobilissimo cristallo. La nostra percezione fu completamente diversa, eppure il vino era lo stesso. Probabilmente avrà avuto effetto il modo con cui i sentori del vino furono sprigionati dal bicchiere, ma certamente ha avuto un ruolo importante la leggerezza e l’eleganza al tatto del bicchiere di cristallo sulla nostra percezione.

Questi elementi, esterni al prodotto, sembrano secondari, ma in realtà possono modificare, o rinforzare, certe sensazioni gustative.

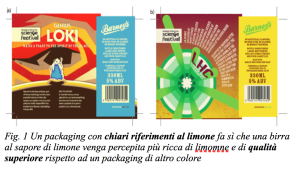

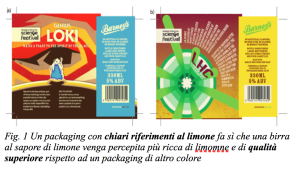

Cosi, per esempio, usando un’etichetta con colori tendenti al gialloverde per una bottiglia di birra al limone (cfr. Fig. 1) la percezione della birra risulta più “limonosa” dello stesso prodotto offerto in una bottiglia con etichetta tendente al marrone e rosso (Barnett, e Spence, 2016). Allo stesso modo, una mousse al cioccolato offerta su un piatto bianco viene percepita un poco più dolce della stessa mousse presentata su un piatto nero (Tu et al, 2016). Ed ancora, uno yogurt mangiato con un cucchino bianco viene percepito un po’ più dolce dello stesso yogurt servito su cucchiaino nero e un caffè e latte bevuto in una tazza di ceramica bianca viene percepito più intenso dello stesso prodotto bevuto da una tazza di vetro trasparente (Spence, 2017).

Non stupiamoci, quindi, se il colore di un’etichetta o di un prodotto possa contribuire a creare aspettative in grado di alterare il gusto di un vino o il suo profumo. Si tratta di meccanismi incontrollati in grado di influenzare anche i più esperti.

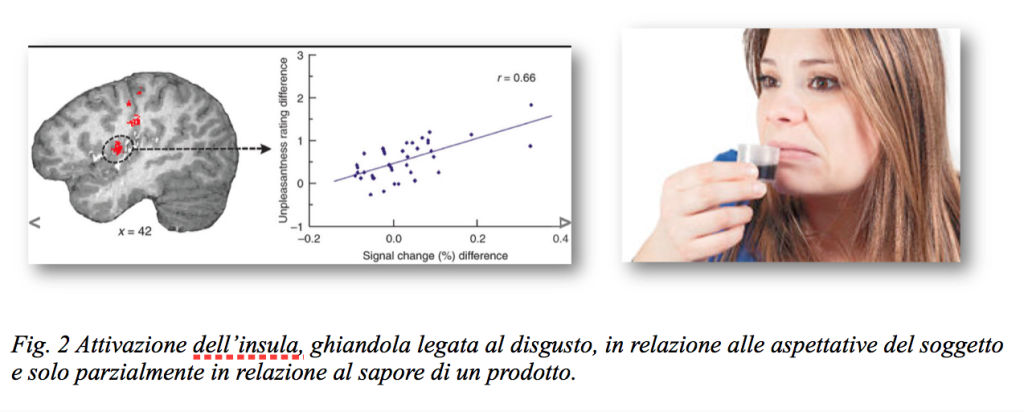

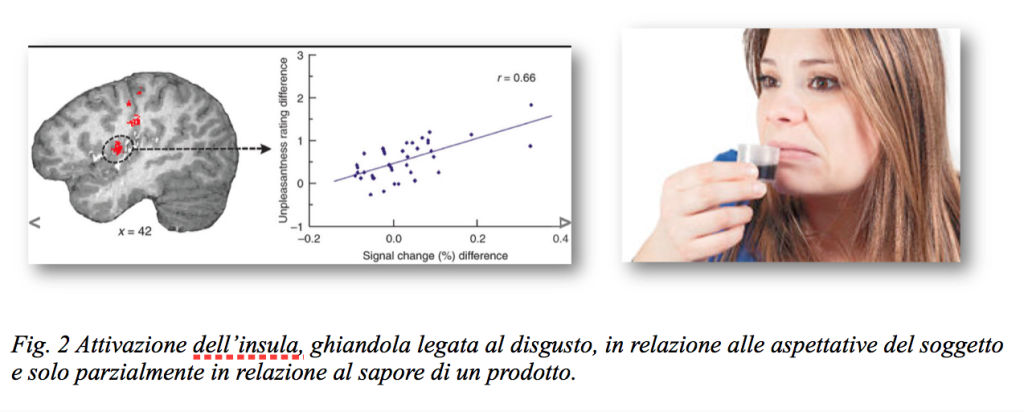

A tal proposito, in un interessante studio condotto presso l’Università di Bordeaux da Morrot et al. (2001) è stato chiesto ad un gruppo di 54 esperti, la valutazione sensoriale due vini: uno rosso e l’altro bianco ma colorato di rosso con enocianina (clorante di rosso inodore ed insapore). La ricerca era finalizzata a valutare l’effetto del colore del vino sulla sua valutazione sensoriale da parte di un gruppo di esperti. I risultati confermarono il ruolo delle aspettative condizionate dalla vista del colore del vino nella percezione dell’odore e del gusto. Le parole utilizzate per descrivere sia il vino rosso che quello bianco (ma colorato di rosso) furono pressoché le stesse. Sappiamo che le due tipologie di vino provocano sensazioni gustative differenti, ma l’effetto delle aspettative condizionate dal colore del vino furono tanto forti da annullare la capacità di riconoscimento sensoriale del gusto e del profumo. Gli autori dimostrarono come il colore del vino avesse indotto all’errore anche i più raffinati esperti, convincendoli sul fatto che i due vini fossero entrambi della stessa tipologia, e quindi passibili di medesima descrizione. In questo caso l’interferenza tra visione e percezione olfattiva e gustativa è stata determinata dal ruolo che ha la corteccia visiva primaria. Attraverso l’immagine rilevata con la PET (Risonanza con Emissione di Positroni) si evince, infatti, come la corteccia visiva abbia un effetto di condizionamento sulla sensazione olfattiva e gustativa poiché la vista è un senso dominante. D’altra parte, sappiamo che il 50% delle cellule del nostro cervello sono dedicate alla vista e solo 1% al gusto. Non si tratta solo dell’effetto della vista. Infatti, facendo assaggiare un liquido ad un gruppo di persone segnalando che si tratta di un liquido molto amaro si rileva conRisonanza Magnetica l’attivazione dell’Insula (ghiandole deputata al disgusto) (cfr. Fig.2). Facendo però assaggiare lo stesso liquido alle stesse persone presentandolo come “meno amaro del precedente” l’attivazione dell’insula è minore e le persone lo percepiscono meno amaro, eppure il liquido era lo stesso (Nitschke et al. 2006).

Oggi grazie alle tecniche neuroscientifiche possiamo valutare l’impatto emotivo provocato dalla scelta cromatica di un prodotto, della sua etichetta o del suo packaging. Lo studio di questi processi rientra all’interno di un nuovo ambito di ricerca denominato NeuroGastrofisica e della Neuroenologia. Si tratta di un ambito che, da una parte, raccoglie i risultati di numerose ricerche di grande interesse per la ristorazione e per il mondo del vino e, dall’altro, apre nuovi campi di studio, connessi al neuromarketing che contribuisce a misurare l’effetto emozionale ed inconsapevole di questi elementi, apparentemente secondari, attraverso tecnologie molto avanzate.

Il sistema olfattivo è infatti strettamente legato ai processi emozionali e mnemonici, anche inconsapevoli. Le molecole odorose provenienti dal sistema ortonasale (naso) e retronasale (bocca) vengono tradotte in vere e proprie “immagini dell’odore” e processate in una prima area, il “Bulbo olfattivo”. Questo ha la funzione di fare passare solo gli odori più intensi e forti. Immediatamente dopo, viene attivata la “Corteccia Olfattiva” (Fig. 3) che, benché si chiami corteccia, non ha nulla di consapevole. Si tratta, infatti, di un’area del cervello deputata al riconoscimento dei profumi già sentiti e memorizzati. In quest’area ritroviamo le nostre tracce mnestiche odorose.

È qui che riconosciamo i profumi dell’infanzia o delle esperienze passate, siano esse gradevoli o sgradevoli. Si tratta di un’area molto prossima al Sistema Limbico, dove l’informazione viene valutata sulla base dell’emozioni che lo stimolo olfattivo è in grado di richiamare. Infine, l’informazione giunge alla “Corteccia Orbito-Frontale”, ovvero quell’area del lobo prefrontale deputata all’elaborazione consapevole delle stimolazioni olfattive.

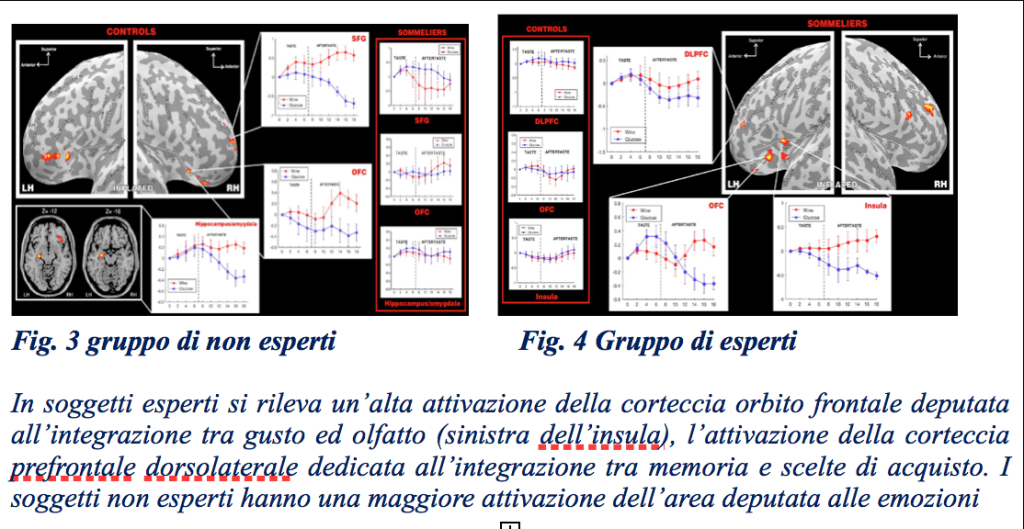

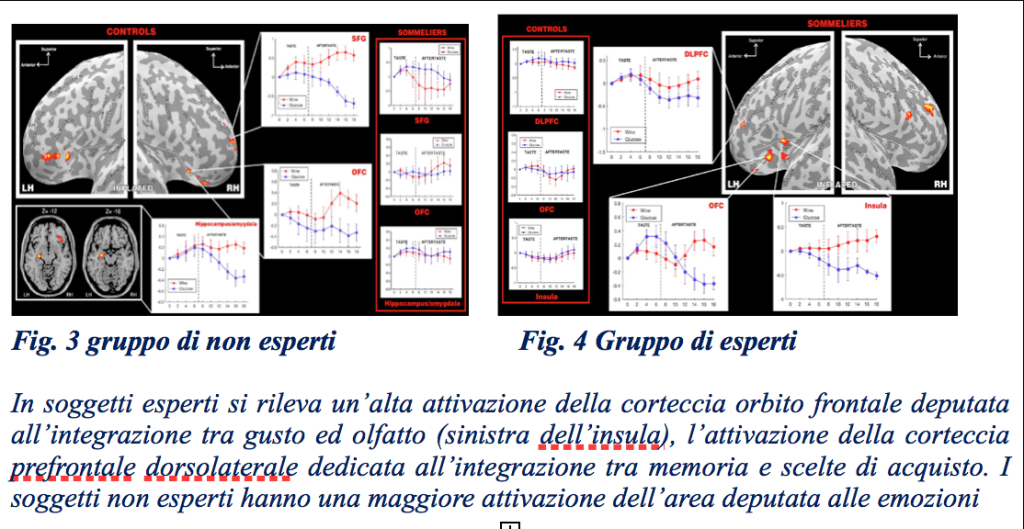

Da una recente ricerca (Castriota_Scanderberg et al. 2005) si evince che quest’area si attiva insieme alla Corteccia Prefrontale Dorsolaterale (deputata alla programmazione e alle azioni consapevoli) molto di più in soggetti esperti che tentano di riconoscere sentori e profumi (Fig.4 come per esempio nei sommelier, e molto meno in soggetti non esperti che si lascerebbero influenzare più dalla dimensione emozionale dello stimolo (Fig. 3). Ciò dimostra l’importante ruolo che le emozioni hanno nel processo olfattivo in questi soggetti e quanto sia importante per loro che, da qualche parte, qualcuno o qualcosa possa dare le giuste informazioni sul tipo di aroma e sui “sentori” dei vini o dei cibi che andranno ad assaggiare.

Castriota-Scanderbeg, A., Hagberg, G. E., Cerasa, A., Committeri, G., Galati, G., Patria, F., et al. (2005). The appreciation of wine by sommeliers: a functional magnetic resonance study of sensory integration. Neuroimage 25, 570–578.

Morrot G, Brochet F, Dubourdieu D (2001), “The color of odors”, Brain and Language, 79: 309–320.

Barnett, and Spence (2016) Assessing the Effect of Changing a Bottled Beer Label on Taste Ratings Nutrition and Food Technology: Open Access

Nitschke et al. 2006 Altering expectancy dampens neural response to aversive taste in primary taste cortex. Nature Neurosciencevolume 9, pages435–442

Spence C. (2017). Gastrophisic: the new science of eating. Viking Editore

How Neurogastrophysics (or how neurosciences) explain the pleasantness of wine

Can the taste of a wine be modified by aspects that have nothing to do with the product itself? In other words, can the perceived quality of a wine be modified by elements external to the product, such as background music or contact with a rough (black sandpaper) or soft (white plush) coaster? As some well-known neurobiologists Morrot, Brochet and Dubourdieu (2001) say, “the taste of a molecule or a mixture of several molecules is built in the brain of a taster”. Indeed, the taste of wine can be influenced by expectations and conditionings that have nothing to do with our taste buds.

Numerous researches have been conducted in this area: from the effect of the colors of a wine to the lights of the place where it is being tasted, from background music during the tasting phase to the shape or consistency of the glass. In this regard, I remember when during a splendid tasting of red wines, at the Cantina del Baglio del Cristo di Campobello in Sicily, the owner made us taste the same wine in two glasses, one of normal glass and one of very noble crystal. Our perception was completely different, yet the wine was the same. The way in which the scents of the wine were released from the glass probably had an effect, but the lightness and elegance to the touch of the crystal glass certainly had an important role on our perception.

These elements, external to the product, seem secondary, but in reality they can modify or reinforce certain gustatory sensations.

Fig. 1 A packaging with clear references to lemon makes a lemon-flavored beer perceived as richer in lemon and of higher quality than packaging of another color

Thus, for example, using a label with colors tending towards yellow-green for a bottle of beer with lemon (see Fig. 1) will be perceived as more “lemony” than the same product offered in a bottle with a label tending towards brown and red (Barnett, & Spence, 2016). Similarly, a chocolate mousse offered on a white plate is perceived a little sweeter than the same mousse presented on a black plate (Tu et al, 2016). Again, a yogurt eaten with a white spoon is perceived a little sweeter than the same yogurt served on a black spoon and a coffee and milk drunk in a white ceramic cup is perceived more intense than the same product drunk from a transparent glass cup (Spence, 2017).

Let us not be surprised, therefore, if the color of a label or a product can help create expectations capable of altering the taste of a wine or its perfume. These are uncontrolled mechanisms capable of influencing even the most expert.

Fig. 2 Activation of the insula, a gland linked to disgust, in relation to the subject’s expectations and only partially in relation to the taste of a product. In this regard, in an interesting study conducted at the University of Bordeaux by Morrot et al. (2001) a group of 54 experts was asked for the sensory evaluation of two wines: one red and the other white but colored red with oenocyanin (odourless and tasteless red chlorinant). The research was aimed at evaluating the effect of the color of the wine on its sensory evaluation by a group of experts. The results confirmed the role of expectations conditioned by the sight of wine color in the perception of smell and taste. The words used to describe both red and white (but colored red) wine were almost the same. We know that the two types of wine cause different gustatory sensations, but the effect of the expectations conditioned by the color of the wine were so strong as to nullify the capacity for sensory recognition of taste and aroma. The authors demonstrated how the color of the wine had led even the most refined experts into error, convincing them that the two wines were both of the same typology, and therefore liable to the same description. In this case the interference between vision, olfactory and gustatory perception was determined by the role played by the primary visual cortex. Through the image taken with the PET (Positron Emission Resonance) it can be seen, in fact, how the visual cortex has a conditioning effect on the olfactory and gustatory sensation since sight is a dominant sense. On the other hand, we know that 50% of our brain cells are devoted to vision and only 1% to taste. It’s not just about the effect of sight. In fact, making a group of people taste a liquid, signaling that it is a very bitter liquid, the activation of the Insula (glands responsible for disgust) is detected with Magnetic Resonance (see Fig.2). However, by having the same people taste the same liquid, presenting it as “less bitter than the previous one”, the activation of the insula is less and people perceive it less bitter, yet the liquid was the same (Nitschke et al. 2006).

Today, thanks to neuroscientific techniques, we can evaluate the emotional impact caused by the chromatic choice of a product, its label or its packaging. The study of these processes falls within a new research area called NeuroGastrophysics and Neuroenology. It is an area which, on the one hand, brings together the results of numerous researches of great interest for the restaurant and wine world and, on the other hand, opens up new fields of study connected to neuromarketing which helps to measure the emotional and unaware effect of these elements, apparently secondary, through very advanced technologies.

The olfactory system is in fact closely linked to emotional and mnemonic processes, even unconscious ones. The odorous molecules coming from the orthonasal (nose) and retronasal (mouth) systems are translated into real “smell images” and processed in a first area, the “olfactory bulb”. This has the function of letting only the most intense and strong smells through. Immediately afterwards, the “Olfactory Cortex” (Fig. 3) is activated which, although it is called the cortex, has nothing conscious about it. It is, in fact, an area of the brain responsible for recognizing the scents already smelled and memorized. In this area we find our odorous memory traces.

It is here that we recognize the scents of childhood or past experiences, whether they are pleasant or unpleasant. This is an area very close to the Limbic System, where information is evaluated on the basis of the emotions that the olfactory stimulus is able to recall. Finally, the information reaches the “Orbitofrontal Cortex”, i.e. that area of the prefrontal lobe responsible for the conscious elaboration of olfactory stimulations.

Fig. 3 group of non-experts Fig. 4 Group of experts

In expert subjects there is a high activation of the orbitofrontal cortex responsible for the integration between taste and smell (left of the insula), the activation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex dedicated to the integration between memory and purchase choices. Non-expert subjects have a greater activation of the area assigned to emotions

Recent research (Castriota_Scanderberg et al. 2005) shows that this area is activated together with the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (responsible for planning and conscious actions) much more in expert subjects who try to recognize scents and perfumes (Fig.4 as for example in sommeliers, and much less in non-expert subjects who would let themselves be influenced more by the emotional dimension of the stimulus (Fig. 3).This demonstrates the important role that emotions have in the olfactory process in these subjects and how important it is for them that, somewhere, someone or something can give the right information on the type of aroma and the “scents” of the wines or foods they are going to taste.

Castriota-Scanderbeg, A., Hagberg, G. E., Cerasa, A., Committeri, G., Galati, G., Patria, F., et al. (2005). The appreciation of wine by sommeliers: a functional magnetic resonance study of sensory integration. Neuroimage 25, 570–578.

Morrot G, Brochet F, Dubourdieu D (2001), “The color of odors”, Brain and Language, 79: 309–320.

Barnett, and Spence (2016) Assessing the Effect of Changing a Bottled Beer Label on Taste Ratings Nutrition and Food Technology: Open Access

Nitschke et al. 2006 Altering expectancy dampens neural response to aversive taste in primary taste cortex. Nature Neurosciencevolume 9, pages435–442

Spence C. (2017). Gastrophisic: the new science of eating. Viking Editore

Récents articles

Stay tuned for new articles and industry trends !

Subscribe to our newsletter and make sure you don’t miss the publication new editions of the magazine!